Celebrating Creativity and Childhood: The Patchwork Bike

The Patchwork Bike

Written by Maxine Beneba Clarke; illustrated by Van Thanh Rudd

Published by Candlewick Press

ISBN # 978-1-5362-0031-7

Grades PreK and up

Book Review

In this Boston Globe-Horn Book award-winning picturebook, a young girl celebrates one of the most simple, yet powerful, facets of childhood—creativity. In The Patchwork Bike, we meet a young girl living in a poor village with a “mud-for-walls home . . . out in the no-go desert, under the stretching-out sky.” And yet, her voice and story are filled with sheer pride and joy. With ingenuity and found materials, she and her “crazy brothers” have built a bike. She admits the bike itself isn’t necessarily a finely crafted vehicle—“It has a bent bucket seat and handlebar branches that shicketty shake when we ride over sand hills”—yet, she proudly declares it as “[t]he best thing in the world to play with.” In the narrator’s point of view, this is no “patchwork bike,” but a slick ride with classic chrome handlebars. Australian author Maxine Beneba Clarke’s text uses simple, yet vivid descriptions full of alliteration and onomatopoeia, that repeat to echo a young child’s uncomplicated worldview. Street art skills and bold paint strokes emphasize the patchwork theme, as illustrator Van Thanh Rudd incorporates ripped corrugation, sealing tape, and other packaging details into the background of each page to simulate cardboard boxes. Both Clarke and Rudd counter a deficit view of poverty, focusing on the possibility, love, and fun the characters experience. Clarke’s author’s note describes how this wonderfully unpretentious book can also be explored as a statement about poverty, while Rudd’s illustrator’s note illuminates the social justice imagery he wove throughout his artwork. In all, The Patchwork Bike a work of literary and visual art to share and explore on multiple levels with your students.

Teaching Ideas and Invitations

Grades K and up

Precise Words and Phrases. Maxine Beneba Clarke’s glorious text is filled with precise words, such as “bashed tin-can handles,” and figurative language, such as “winketty wonk”. Help students do a close reading of the text, noting how those language choices enhance the content of the story. Have students identify the lines they like best, making sure they explain how the words and language in those lines make them feel and what they make them think. Then, have them try emulating what they like in Clarke’s text within their own writing.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Cardboard Picturebooks. Van Thanh Rudd’s clever illustrations reflect the notion of patchwork creations, simulating street art painted onto cardboard scraps. In this vein, gather a set of random, found, and unexpected art supplies, such as aluminum foil swatches, twigs, and shredded paper from the recycling bin, as well as cardboard for the pages. Have students create a book and illustrations, for either their own written pieces or for texts written by another author, from these materials. Display their works of literary and visual art in the school’s hallway and library display cases, along with an illustrator’s note explaining the materials used and inspiration for the illustrations and book design.

Patchwork Makerspace Creations from Found Materials. Discuss what the term “patchwork” means when describing how something is made and what the term “found” means when describing materials. Challenge students to use their creativity, just as the protagonist and her siblings do in The Patchwork Bike, to use found materials to construct something patchwork that they wish for or that they think would make life easier for people. Consider allowing students to work in small groups or with their families. Share The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer; With My Hands: Poems about Making Things, by Amy Ludwig VanDerwater, and some articles about homemade and patchwork inventions that are easy to make at home to inspire your students. Explore some of the websites listed below in Further Explorations about how bicycles are made, as well. Collaborate with the STEAM teachers in your school to hold a patchwork creations fair.

Bikes and Childhood. In her Author’s Note, Maxine Beneba Clarke states that “Most kids have a bike have seen a bike, or have longed for a bike.” In fact, many children’s books feature this iconic symbol of childhood. Gather a text set of books that feature children riding bikes, asking your school or local librarian for help, if needed. Depending on your students’ grade level, some titles you might want to share include Ben Rides On, Merci Suárez Changes Gears, Fast Enough: Bessie Stringfield’s First Ride, Emmanuel’s Dream: The True Story of Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah, and even On a Beam of Light: A Story of Albert Einstein. What role does the bike play in each story? How does the bike represent the child protagonist’s outlook, hopes, dreams, and goals? Ask students to reflect on what a bike means to each of them. Encourage students to express this meaning in writing, in any genre they choose, or in any modality they choose. Create a class showcase where students share what they’ve created to express what bikes mean for their individual childhoods.

Books about Play and Imagination. As Maxine Beneba Clarke explains in her Author’s Note, the power of play and imagination is important “in terms of being able to imagine yourself out of poverty and look for a better future.” With the help of your school or local librarian, gather a text set of books about play and imagination that showcase the power they harness to envision change. Some examples include The Nowhere Box, by Sam Zuppardi; Imagine!, by Raúl Colón; Imagine, by Juan Felipe Herrera, The Banana-Leaf Ball: How Play Can Change the World, by Katie Smith Milway, and for older students, The Cardboard Kingdom, by Chad Sell; Doll Bones, by Holly Black, and Bridge to Terabithia, by Katherine Paterson. With your students, create a list of the benefits of play and imagination and consider where opportunities for each exist within the school day. If there aren’t enough, encourage students to conduct more research and present the school faculty and administration with their findings to advocate for more play and imagination time at school.

Author’s Notes as Mentor Texts. Share Maxine Beneba Clarke’s Author’s Note with your students, paying special attention to what she says about her inspiration and her hopes for the book. Have students reflect on pieces of their own writing where they were able to choose the topic—perhaps a personal narrative, perhaps a poem, perhaps an expository essay or “all about” piece. Guide them to articulate what inspired them to write each piece was, as well as what their hopes for each piece is. Reread Clarke’s note, as well as authors’ notes in other books, in order to determine common elements and information that’s found in them. Help students identify what makes an author’s note distinct from the rest of the text. Finally, have students add an author’s note to at least one of the pieces they have already written, and then encourage them add author’s notes to more pieces throughout the school year.

Illustrator’s Note. Street artist Van Thanh Rudd’s Illustrator’s Note reveals the multiple layers of meaning he incorporated into the illustrations for The Patchwork Bike, particularly the political imagery present in the scene with the police car and the picture of the bike’s license plate. Discuss with students the difference between what some children’s literature scholars identify as picture books (two words, where the illustrations may merely mirror the information presented in the written text) and picturebooks (one word, where the illustrations provide additional layers of meaning that are not expressed in the written text). Have students go back through Rudd’s illustrations to identify the symbols and additional elements folded into them. Then, engage students in a discussion and exploration about how picturebook illustrations, like murals and street art, can be expressions of activism, as Rudd explains.

Critical Literacy

Picturebook Illustrations as Activist Statements. In his Illustrator’s Note, Van Thanh Rudd explains that the freedom that Maxine Beneba Clarke granted him in illustrating The Patchwork Bike allowed him to make connections between the pride that communities with limited resources have and histories of rebellion. Engage students in a discussion about whether activist illustrations are appropriate for children’s picturebooks, and why. What are the pros and cons of such illustrations? What is or should be the goal of picturebooks? What other picturebooks might be considered activist statements? How influential might these books be?

Further Explorations

Online Resources

Maxine Beneba Clarke’s Twitter feed

Van Thanh Rudd’s website

The Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards

https://www.hbook.com/boston-globe-horn-book-awards/

Articles about Homemade Bicycles in Rural Settings

https://www.wbur.org/npr/200428557/in-rural-uganda-homemade-bikes-make-the-best-ambulances

Science Channel – How Steel Bicycles are Made

https://www.sciencechannel.com/tv-shows/how-its-made/videos/how-steel-bicycles-are-made

Exploratorium – Science of Cycling: History of Bicycle Frames

https://www.exploratorium.edu/cycling/frames1.html

Popular Mechanics – DIY Commuter Bike Mods

https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/a6133/diy-commuter-bike-mods/

Sciencing –Homemade Inventions

https://sciencing.com/easy-homemade-inventions-5783722.html

https://sciencing.com/make-inventions-kids-homemade-things-8451074.html

Books

Black, H. (2013). Doll bones. New York: Margaret Mc Elderry Books.

Colon, R. (2018). Imagine! New York: Paula Wiseman Books.

Davies, M. (2012). Ben rides on. New York: Neal Porter Books.

Flyte, M. (2016). Box. Ill. by R. Beardshaw. Nosy Crow.

Gill, J. C. (2019). Fast enough: Bessie Stringfield’s first ride. The Lion Forge.

Herrera, J. F. (2018). Imagine. Ill. by L. Castillo. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Lamug, K. K. (2012). A box story. RabbleBox.

McLerran, A. (1991). Roxaboxen. Ill. by B. Cooney. New York: Lothrup, Lee & Shepherd.

Medina, M. (2018). Merci Suarez changes gears. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Portis, A. (2007). Not a box. New York: HarperCollins.

Powell, S. (2014). The cardboard box book: Make robots, princess castles, cities, and more! Ill. by B. Sido. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Rau, D. M. (2001). A box can be many things. Children’s Press.

Russo, M. (2000). The big brown box. New York: Greenwillow.

Sell, C. (2018). The cardboard kingdom. New York: Knopf.

TenNapel, D. (2012). Cardboard. New York: Graphix.

Thompson, L. A. (2015). Emmanuel’s dream: The true story of Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah. Ill. by S. Qualls. New York: Schwartz & Wade.

Yolen, J. (2016). What to do with a box. Creative Editions.

Zuppardi, S. (2013). The nowhere box. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Filed under: Awards, Fiction, Fiction Picture Books, Picture Books

About Grace Enriquez

Grace is an associate professor of language and literacy at Lesley University. A former English Language Arts teacher, reading specialist, and literacy consultant, she teaches and writes about children’s literature, critical literacies, and literacies and embodiment. Grace is co-author of The Reading Turn-Around and co-editor of Literacies, Learning, and the Body.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

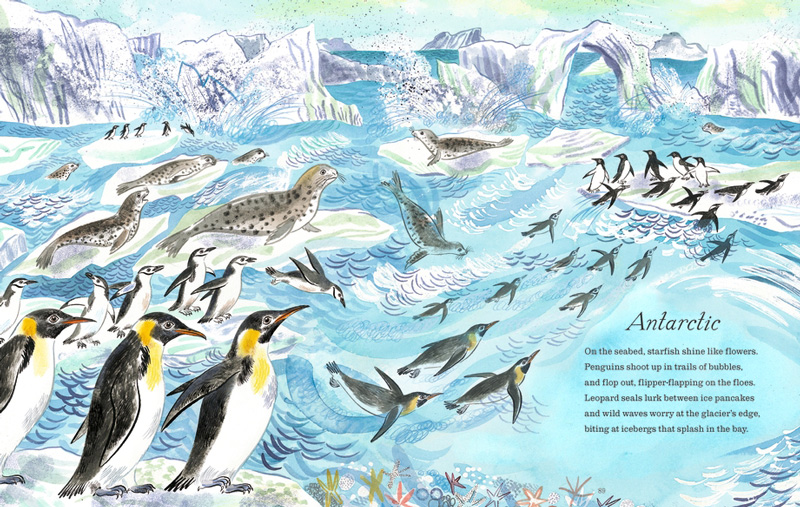

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

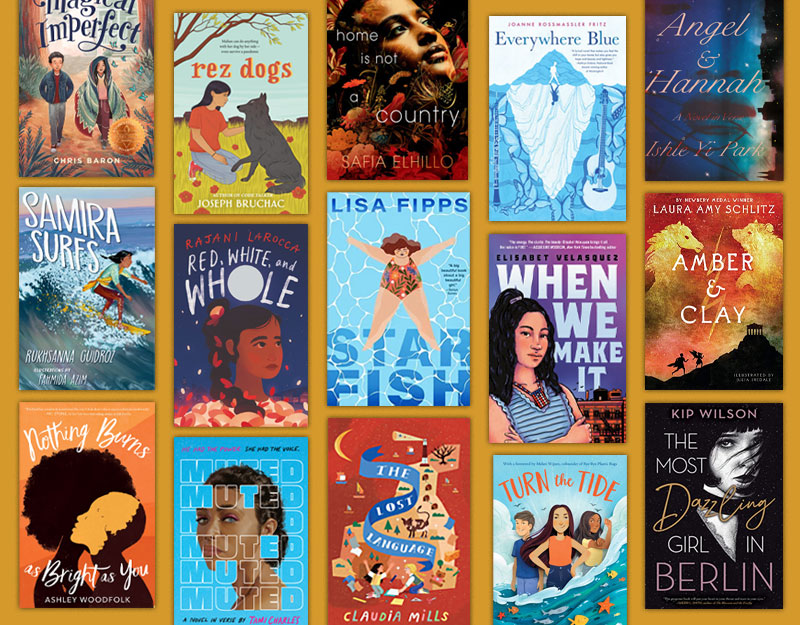

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT