What We Believe Matters Most When Selecting Books

This is our first official entry with The School Library Journal Blog Network, and we are overjoyed and proud to be a part of this community. At The Classroom Bookshelf, we like to take the time at the start of the school year to reflect on what matters most in our classrooms and in bringing literature to life for students. In the fall of 2014, as our country mourned the loss of life and racial divides following events in Ferguson, Missouri, we focused on Teaching for Change and Social Justice. In the fall of 2015, we wrote about Building Classroom Libraries where we offered tips such as questioning leveled systems, creating a balance of genres, and incorporating picture books. This year, we collectively discussed what matters most when it comes to text selection at the book level. We are frequent patrons of our local libraries and bookshops and we thought teachers and librarians might like to peek inside our heads to better understand our process when we are staring at the shelves or searching online deciding what to share with you each week.

This is our first official entry with The School Library Journal Blog Network, and we are overjoyed and proud to be a part of this community. At The Classroom Bookshelf, we like to take the time at the start of the school year to reflect on what matters most in our classrooms and in bringing literature to life for students. In the fall of 2014, as our country mourned the loss of life and racial divides following events in Ferguson, Missouri, we focused on Teaching for Change and Social Justice. In the fall of 2015, we wrote about Building Classroom Libraries where we offered tips such as questioning leveled systems, creating a balance of genres, and incorporating picture books. This year, we collectively discussed what matters most when it comes to text selection at the book level. We are frequent patrons of our local libraries and bookshops and we thought teachers and librarians might like to peek inside our heads to better understand our process when we are staring at the shelves or searching online deciding what to share with you each week.

In some ways, our process is very simple. We turn to books that inform us, intrigue us, move us, and that stay with us long after we finish the last page. We notice book covers that are aesthetically captivating and that already beg us to ask questions about what the book is about, what is going to happen, or what new kinds of knowledge we can gain by reading on. We read reviews, blogs, and newsletters to identify the new titles that are generating discussion. We also imagine the faces of students and consider whether they will lean in more closely to listen to a book read aloud or whether they will get lost in the pages as they independently explore the book on their own.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In other ways, our process is complex in terms of the ways we consider multiple dimensions when deciding how a book can come to life in a classroom. When we open a book, we start noticing and naming all of the ways we could deepen student learning and inspire a room full of readers, writers, and creators. We also strive to spotlight books across genres including fiction, narrative nonfiction, expository/non-narrative nonfiction, and poetry. Additionally, we are committed in our shared belief that we need more diverse representations of society on classroom bookshelves. As such, we aim to select books that include characters from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds authored and illustrated by culturally and linguistically diverse authors. The following are four key areas that we find important to consider when deciding whether a book is a new must-have for our collections and that we want to share with you through our reviews and teaching invitations each week:

Text Selection to Engage Literacy Learners

As we select the books that we use in our classrooms, the learners with whom we work are at the forefronts of our minds. LIke you, we have taught in classrooms that include children with a wide range of cultural, social, academic, and emotional experiences. We know that the texts we include in the classroom need to be similarly varied so that each child has reading material that motivates, intrigues, and inspires. Keeping our readers in mind, we evaluate books for their quality, their complexity, and their utility (Cappiello & Dawes, 2015). We consider whether the book tells a compelling story; includes a character with whom students can identify or whom they can learn from; helps children to better understand the social or scientific dimensions of their world; or inspires children to think like historians, mathematicians, or scientists. We also look closely at the language of the text. What kind of writing is this? Is it lyrical, informative, playful, evocative, clever? We consider the content and language in relation to the developing readers in our classrooms. How has the author used language to make the content more accessible? What do readers need to know to access and comprehend this particular text? Finally we consider how we will use the text. Is it a text that we want all of the readers in our class to experience through a read aloud? Does the text offer an opportunity to extend or reinforce content knowledge for small groups of readers in the class? Will the text appeal to a subset of readers who will enjoy a lively discussion in a literature circle? Or might this be the perfect book to offer an individual reader because it is so well matched to his/her personal interests. We believe that you, as teachers and librarians can make powerful text choices for your students precisely because you are the ones who know your students best. With each book that we feature in The Classroom Bookshelf, we aim to provide you with an array of teaching ideas that you, as curriculum designers, can customize for the learners in your classrooms.

Curriculum Connections

We believe that high quality children’s and young adult books have an important role to play across the curriculum and the school day. It is essential that classroom collections offer readers rich opportunities to select texts of interest to them. But it is equally important that teachers select quality and engaging books for the curriculum that they create in language arts, social studies, science, mathematics, and the related arts. When we write our entry each week, we write to teachers and librarians directly, to allow you inside our heads as we consider the many opportunities each book offers for classroom exploration in a range of curricular contexts.

Quality literature can be used in language arts, for guided reading, independent reading, literature circles and book clubs, and whole class explorations. In reading and writing workshop, literature of all genres allows students to explore the writing process, literary elements, theme, and genre. Novels such as Wild Robot, The Mighty Miss Malone, The War the Changed My Life, and The Red Pencil can be read concurrently in small groups to explore the theme of survival. Well-written books offer diverse opportunities for vocabulary instruction in engaging contexts. Both Over in the Wetlands, a fictional book about wetlands during hurricanes, and One Today, an inaugural poem in picture book format that serves as a love song to America, model the use of vivid verbs.

Quality literature also serves as a catalyst for rich explorations in the content areas. Fiction, nonfiction, and poetry can all be used to explore content and model disciplinary ways of questioning, knowledge-building, and problem-solving. Nonfiction picture books such as Separate is Never Equal and The First Step: How One GIrl Put Segregation on Trial introduce elementary-aged students to the complexity of school segregation at different times in our history, and provide opportunities to examine issues of equity today. Marc Aronson’s nonfiction book The Griffin and the Dinosaur models how a new field of science, geomythology, emerged from history and myth, while his Skull in the Rock demonstrates how scientists’ understanding of human evolution shifts with each new discovery. Nonfiction picture books Raindrops Roll, All the Water in the World, and Water is Water offer different snapshots of the water cycle. Finally, well-researched books offer readers a window into the inquiry process and a pathway to their own research, as we see in Deborah Hopkinson’s historical novels A Bandit’s Tale and The Great Trouble.

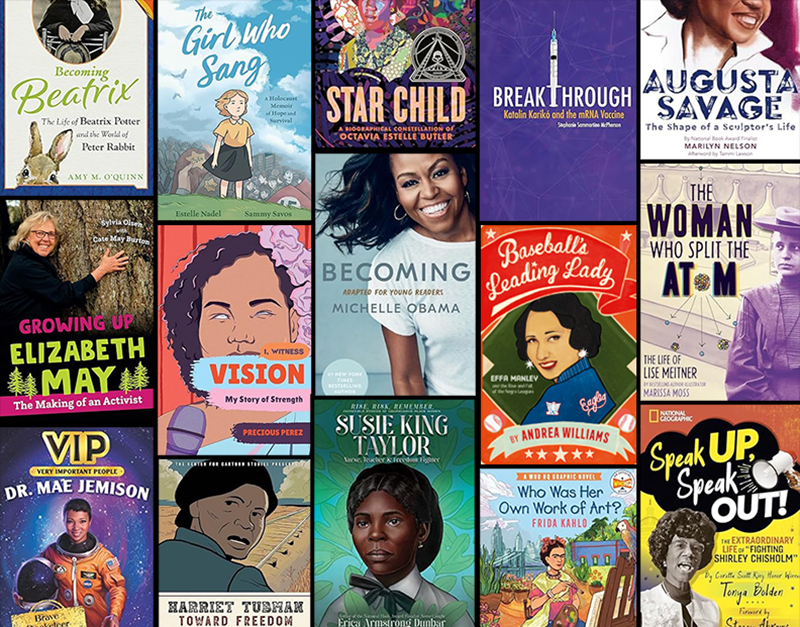

Authentic Representation

The notion of authentic representation in children’s literature is increasingly at the forefront of the field, with nonprofit organizations, libraries, and book publishers attempting to address the glaring void of children’s and young adult literature that are about or written by diverse populations and perspectives. As teacher educators, this matter is of our utmost concern if we want children to perceive books as tools and resources for their personal, intellectual, and social growth. How can they do that–and how can we tell them convincingly–if the books they encounter day after day in schools are about children who don’t look, act, or speak like them? According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, of the approximately 3,200 books published in 2015 and received from U.S. children’s book publishers, only 14% were about people of color and First/Native Nations, with only about 10% written by them. While this is an improvement from the 10% average that children’s publisher Lee & Low reported in 2013, the number is still abysmal considering that the U.S. Census Bureau reports over 30% of the U.S. population are people of color and First/Native Nations. Moreover, the National Center for Education Statistics reported a demographic milestone for U.S. public school classrooms: children of color and First/Native Nations comprise more than 50% of students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools. That percentage is projected to continually increase over the next ten years,

But race and ethnicity aren’t the only kinds of representation that concern us. Issues of diversity relating to gender, socioeconomic class, religion, etc. are real matters for students, too. Although we forefront texts that lend themselves well to disciplinary curricula, we firmly believe that the less often articulated goal of helping readers find their place in the world and grow their possibilities in life is equally vital. To quote one of our heroes, acclaimed social justice educator Sonia Nieto, we seek to share “more balanced, complete, accurate, and realistic literature that asks even young readers to grapple with sometimes wrenching issues” (1992, p. 188). We therefore also seek to spotlight texts that attempt to reconcile the story gap (Cunningham & Enriquez, 2015) with authentic representations of subject, protagonist, language, illustration, author, and illustrator. In our Teaching Ideas and Invitations for each book, especially in those labeled “Critical Literacy,” we suggest learning experiences for students that help them recognize and value diverse perspectives, interrogate the representations and perspectives present in the text and/or illustrations, and further investigate issues around authentic representation.

The Value of Social-Emotional Connections

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Perhaps not surprisingly, studies such as one at The New School in New York City, have found that reading literary fiction strengthens a reader’s capacity to empathize or understand what others are thinking and feeling. Many of the texts we select are because they are character-driven narratives that lead us to empathize with characters’ struggles and complicated inner lives. This includes characters in fictional books as well as figures in biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs. These are characters like Jackson who shares his inner dialogue about his family becoming homeless in Katherine Applegate’s beautiful novel, Crenshaw, and Josh in The Crossover by Kwame Alexander whose identity as a basketball star is expanded as we learn more about his family and fears through his poetry. These are books that feel real as if the main character could be our neighbor or friend. In this way, we connect emotionally often from the first few pages. We also tend to be drawn to books that challenges our own assumptions and undermine stereotypes such as Brown Girl Dreaming, the National Book Award winning memoir-in-verse by Jacqueline Woodson that portrays Woodson’s childhood as an African American girl across time and place. Woodson helps readers question single story depictions of cultural events and the experiences of African American girls through her vivid descriptions of her own hopes, dreams, and everyday challenges. We believe that when we feel things strongly those are often the life moments where we learn something about understanding people different from ourselves as in the books A Boy and a Jaguar by Alan Rabinowitz who overcomes a life struggle with a stutter to become an advocate for endangered animals. As teacher educators, we are also united in our hopeful stance towards teaching and learning. Books like the 2015 Newbery Award winner Last Stop On Market Street by Matt de la Peña are inherently hopeful and help us more mindfully notice beauty in unexpected places in our everyday worlds. We emphatically believe that fiction, as well as nonfiction, poetry, and other genres teach us things about ourselves, others, and the world and that books serve as bridges for social-emotional understandings in our classrooms. In this way, we argue that content must be coupled with care if students are to feel valued and supported in their own daily struggles whatever they may be.

Looking Ahead

This fall, we will continue to post a new entry each Monday. The majority of our entries will focus on one book and the many different ways it can be used in the classroom. But every so often we will focus on a particular topic, and offer a range of titles to consider for classroom use.

Even though we blog book-by-book, we hope that you will see the connections across books, and the ways they can be used collectively in your classroom, as we have tried to demonstrate here. It is our wish that this archive of over 200 books is as useful to you as the next forty or so books that we will write about this school year.

References

Cappiello, M.A. & Dawes, E.T. (2015). Teaching to complexity. Huntington Beach, CA: Shell Education.

Cunningham, K., & Enriquez, G. (2015, November). Closing the story gap: Supporting all students to see themselves in texts. Presentation at the Annual Literacy for All Conference, Providence, RI.

Nieto, S. (1992). “We have stories to tell: A case study of Puerto Ricans in children’s books.” In Harris, V.J. (Ed.), Teaching Multicultural Literature in Grades K-8. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc.

Filed under: Classroom & Curricular Ideas

About Katie Cunningham

Katie is a Professor of Literacy and English Education at Manhattanville College. There she is also the Director of the Advanced Certificate Program in Social and Emotional Learning and Whole Child Education. Her work focuses on children’s literature, joyful literacy methods, and literacy leadership. Katie is the author of Story: Still the Heart of Literacy Learning and co-author of Literacy Leadership in Changing Schools. Her book Start with Joy: Designing Literacy Learning for Student Happiness will be released September 2019. She is passionate about the power of stories to transform lives.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Team Unihorn and Woolly | This Week’s Comics

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

So true! Looking forward to your Monday features, Katie :).